Understanding the time signature in music is one of the most useful skills a musician can learn. Whether you read sheet music, accompany a singer, compose a piece, or simply want better rhythmic control at the piano, a clear grasp of time signatures will transform how you hear and play music. This guide explains what a time signature is, how time signatures work on the piano when reading and performing, the most common and some obscure time signatures, practical tips for playing them on the piano, and a short FAQ to answer the questions students ask most often.

What Is a Time Signature?

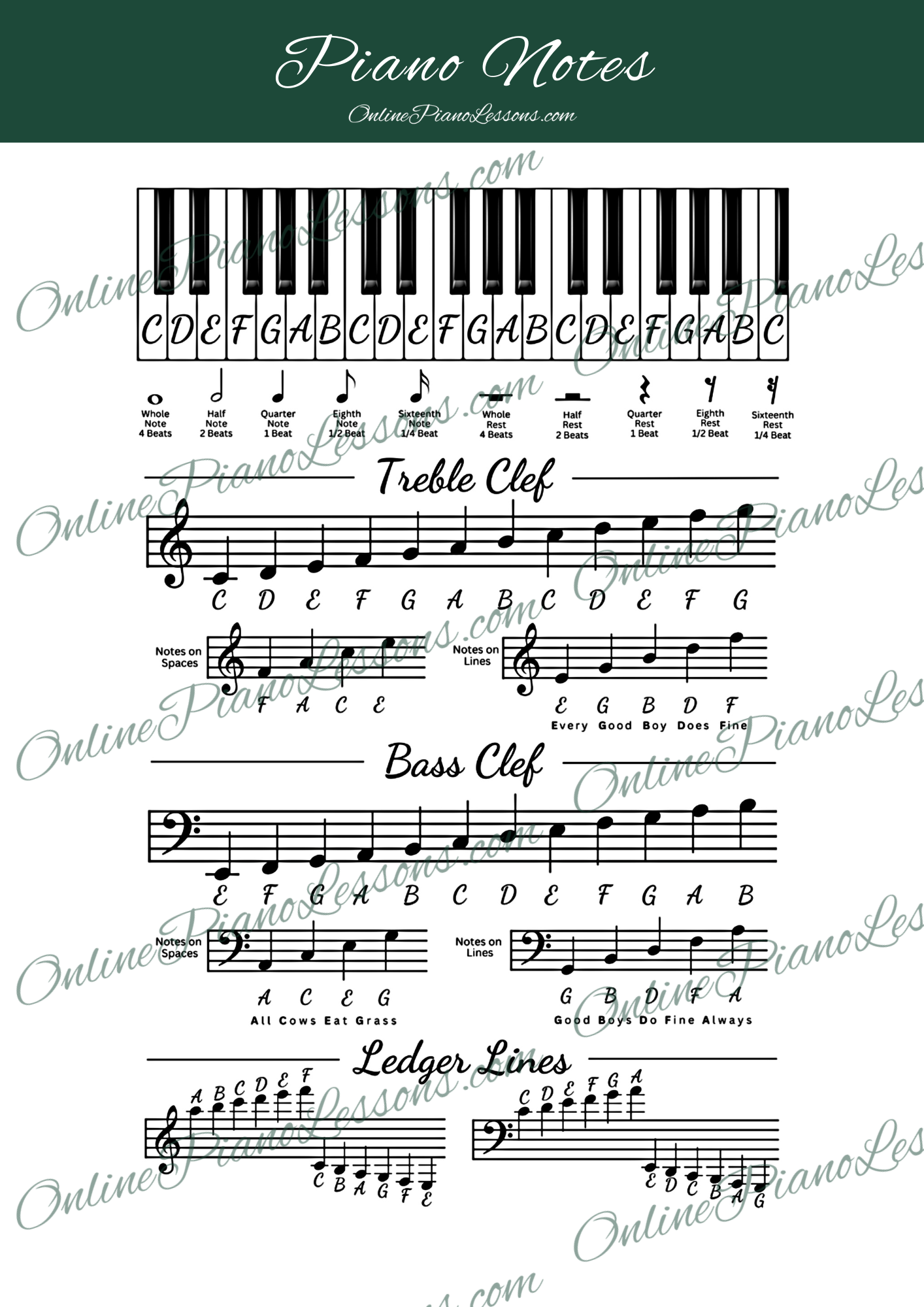

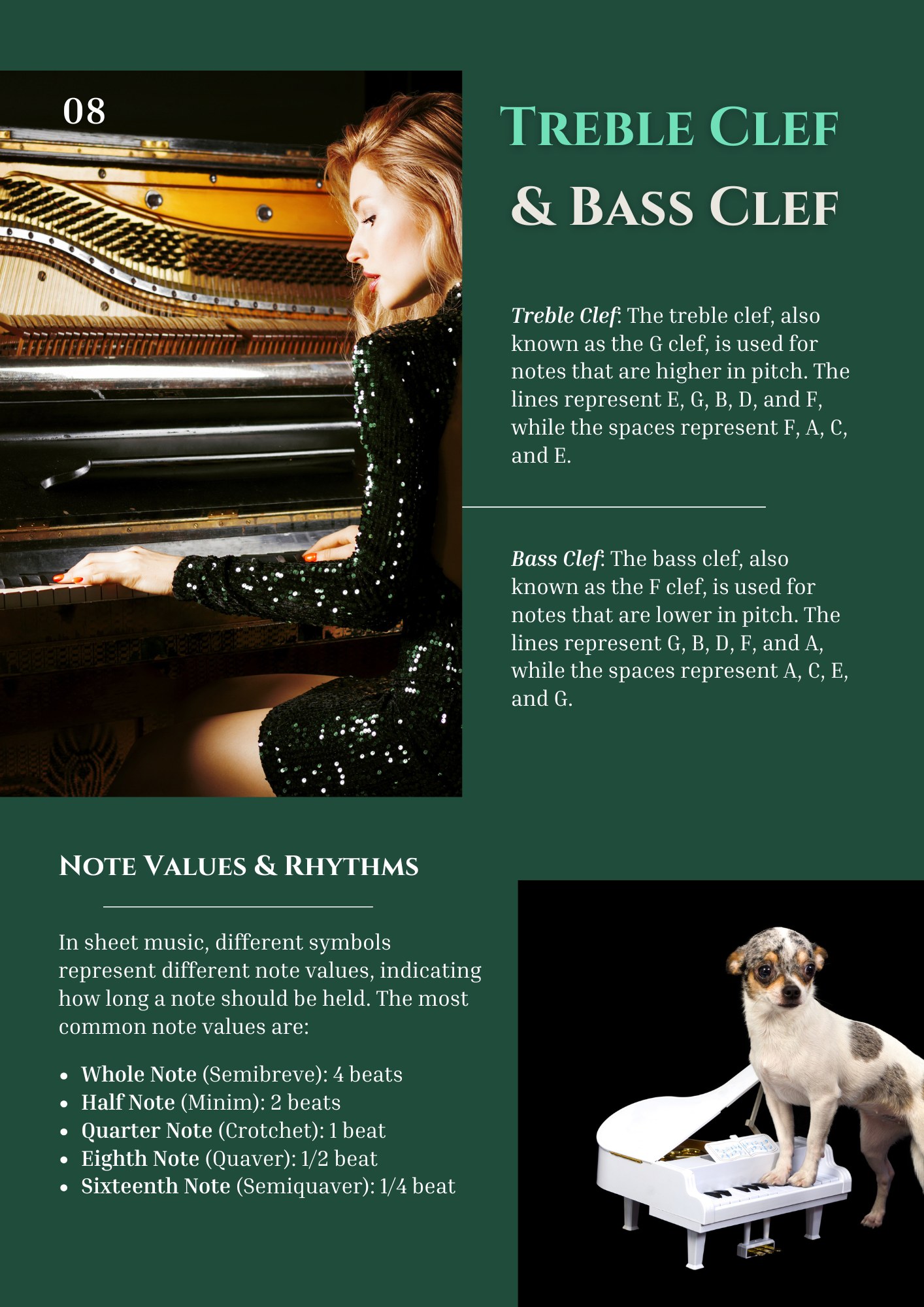

A time signature is the pair of numbers at the beginning of a staff that tells you how the rhythm of a piece is organized. When you open sheet music, the time signature in music appears right after the clef and key signature. The top number of a time signature tells you how many beats there are in each bar (measure). The bottom number indicates which note value receives one beat—4 stands for quarter notes, 8 for eighth notes, 2 for half notes, and so on.

When composers write a time signature in music they are giving a rhythmic framework: how many pulses to count, and what kind of pulse to feel. A simple example is 4/4: four quarter-note beats per bar. That same idea applies whether you see a 3/4 waltz, a 6/8 jig, or a tricky 7/8 progressive tune.

Reading Time Signatures on the Piano

For pianists, reading a time signature in music is the first step toward correct rhythm and phrasing. At the piano you will use the time signature to:

- Count the beats with your left hand while playing melody with your right hand.

- Establish where chord changes occur by aligning left-hand harmony with the bar lines determined by the time signature.

- Shape phrasing: a 3/4 time signature in music suggests naturally grouped phrases of three beats, while a 4/4 time signature suggests four-beat phrases.

When practicing, always say the beat out loud: “1–2–3–4” for a 4/4 time signature, or “1–2–3” for a 3/4 time signature. For compound meters like 6/8 or 12/8, feel the pulse in groups (e.g., two groups of three for 6/8). This spoken counting helps internalize how the time signature in music divides the measure and informs your touch and articulation on the piano.

Common and Obscure Time Signatures

Some time signatures are everywhere; others are rare but musically inspiring.

Common time signatures:

- 4/4 (common time) — four quarter-note beats per bar; a safe default for many piano genres.

- 3/4 — three quarter-note beats; typical for waltzes and many classical pieces.

- 2/4 — two quarter-note beats; common in marches.

- 6/8 — compound duple meter; often felt as two beats subdivided into three, popular for folk and ballad styles.

Obscure time signatures:

- 5/4 (e.g., “Take Five”) — an extra beat gives a lopsided, compelling groove.

- 7/8 or 7/4 — combines groupings such as 2+2+3 or 3+2+2, useful for progressive and Balkan music.

- 11/8, 13/8, and higher odd meters — often found in modern classical or world music, where the time signature in music becomes a compositional device for tension.

Even inside an otherwise straightforward piece, composers sometimes change the time signature in music mid-composition to signal a shift in feeling or rhythm. As a pianist, spotting those changes and preparing for them is essential.

How Time Signatures Affect Piano Technique and Accompaniment

On the piano, the time signature dictates more than counting; it affects technique and arrangement decisions.

Left-hand patterns: In a 4/4 time signature, pianists often play block chords on beats 1 and 3 or steady broken chords across all four beats. In 6/8, left-hand accompaniment usually follows a two-beat feel with arpeggios or bass–chord patterns that emphasize the dotted-quarter pulse.

Voicing and spacing: The time signature in music often suggests spacing of harmonies. For example, in slow 3/4 pieces you may hold sustained left-hand notes while the right hand decorates the melody. In faster 7/8 or 5/4 tunes you might arrange the left hand to play driving bass figures that lock in with the unusual beat groupings.

Rests and syncopation: Reading the time signature in music helps you place rests correctly and understand where syncopations will occur. Syncopation can sound confusing until you understand how the time signature defines the strong and weak beats.

Pedaling: Time signatures also affect pedal usage. In slower meters with longer beats, sustaining pedals are used to connect long tones. In compound or irregular time signatures, more precise pedaling is often necessary to avoid blurring the rhythmic articulation.

Practice Strategies for Mastering Time Signatures on the Piano

- Count aloud. Always count the underlying beat indicated by the time signature in music. Say “1 and 2 and” for subdivisions if needed.

- Clap first. Clap the rhythmic pattern while counting the time signature, then transfer to the piano.

- Subdivide. For complex time signatures, break the bar into smaller groups (e.g., 7/8 as 2+2+3). This makes the time signature in music manageable and musical.

- Use a metronome. Start slow, lock the beat, and gradually increase tempo. The metronome makes the time signature in music feel steady.

- Isolate hands. Practice left-hand accompaniment according to the time signature, then add the right-hand melody once comfortable.

- Practice metric modulation. Move simple melodies between 3/4 and 6/8 feel to internalize how different time signatures relate.

Consistent, focused practice of these techniques will build rhythmic confidence and fluency at the piano.

FAQ

What is the difference between a time signature and tempo?

A time signature tells you the beat structure of each measure; tempo tells you how fast those beats occur. Both are essential when reading a time signature in music.

How do I count compound time signatures like 6/8 on the piano?

Feel 6/8 as two main beats, each subdivided into three: “1 la li 2 la li.” This makes the time signature in music feel natural and dance-like.

Can I change the time signature while playing?

Yes, composers change time signatures to create contrast. As a pianist, watch the score for changes and rehearse the transition slowly.

Are time signatures always written as two numbers?

Typically yes; the top and bottom numbers together form the time signature. Some scores use symbols like “C” (common time, equivalent to 4/4) or a cut time sign (¢ for 2/2).

How do I approach practicing odd meters like 5/4 or 7/8 at the piano?

Group the beats into smaller, logical units (e.g., 5/4 as 3+2 or 2+3) and practice those groupings until they feel natural. Counting and clapping the grouping helps the time signature in music make sense.

Hi, I'm Thomas, Pianist Composer,

Hi, I'm Thomas, Pianist Composer,  I love playing piano, creating new melodies and songs, and further developing my online piano course and making updates/additions to my site OnlinePianoLessons.com!

I love playing piano, creating new melodies and songs, and further developing my online piano course and making updates/additions to my site OnlinePianoLessons.com!  Now that is what I call fun!

Now that is what I call fun!